Carlos Herrero: «The development of the primary sector in Galicia involves producing quality products»

In the food and gastronomy sector, Galicia currently has 37 designations of origin or protected geographical indications. This fact, placed in the context of the socioeconomic transformation that our territory is undergoing, highlights the importance of food excellence for the country's primary sector.

In the same way, science plays a decisive role in the consolidation, verification and validation of these food distinctions that are so valuable for the population as a whole. Something that Carlos Herrero Latorre can talk about at length.

Co-founder of the company AMSLab, professor of Analytical Chemistry at Campus Terra and, for almost a decade, Vice-Rector of Coordination of the Lugo Campus, among many other things... His professional career could not be more transversal and multidisciplinary, qualities that are extraordinarily valued in these times.

Today we invite you to read his reflections on the interesting universe of analytical chemistry, its relationship with the Galician primary sector, his entrepreneurial side or the challenges that universities will face with the arrival of disruptive technologies.

-Your career in the universe of analytical chemistry began at the University of Santiago de Compostela. What led you to specialize in this field, and how has your work evolved since then?

-In the second year of my degree, I had an analytical chemistry subject that really caught my attention. We could say that it was at that moment that I decided to explore this area and make it my field of specialization.

Indeed, this is a discipline that has evolved a lot in recent years, so to speak. There are two or three major milestones in the history of general chemistry, but also in the history of analytical chemistry, that I would like to highlight.

The first is when alchemy became chemistry in all its forms at the end of the 18th century with Lavoisier, considered the father of modern chemistry. At that moment the concept of measurement was really introduced into chemistry: we began to weigh and calculate quantities, giving a measurable dimension to this field.

The second great evolution or revolution was the development of new instrumentation after the Second World War, applicable to common chemistry. And finally, the third milestone I was lucky enough to experience first-hand. It happened in the 70s and 80s, and it was the incorporation of computers into chemical instruments. This allowed for their control, the analysis of the results and the handling of an enormous amount of data, with the ultimate goal of extracting useful information.

The incorporation of computer systems also allowed us to work in a multivariable mode. That is to say, before we worked variably, we measured one thing, and that was it. Now, both in chemical analysis and in the analysis of results or mathematical analysis, chromatographic techniques allow us to determine a very large set of different substances in the same sample, obtaining a large amount of data in a short time.

This, in broad terms, is the evolution of chemistry up to the present day. In fact, it seems that the fourth historical milestone is about to happen: the consolidation of artificial intelligence in analytical chemistry. For example, something that looks promising for this field and that has been underway for some time is neural networks.

-You have published dozens of articles in prestigious journals. What do you consider to be your main contributions to the field of analytical chemistry? Is there any research or contribution that you are particularly proud of?

-I would say that there are three lines in which we carry out most of our research. The first is the characterization of quality agri-food products. We have worked with wine, honey, meat, milk... Practically, all Galician products that have a quality seal. Why? Because we understood that the development of the primary sector in Galicia depends on the production of quality products.

In many cases, we cannot compete on quantity. Therefore, it was clear to us from the beginning that we had to compete on quality, and to compete on quality, we had to classify the product. We had to have systems based on non-subjective tools, on measurable tools that would allow us to identify, without any doubt, whether or not a certain product was of a designation of origin or whether or not it met the requirements of that designation, for example.

This is the first line of work with which I am really very happy, as it allowed us to collaborate directly with many companies that are key to the Galician economy.

The second element that I would like to highlight is the use we made of chemometrics throughout our career. Chemometrics is, in a nutshell, the use of mathematical, statistical and formal logic techniques applied to chemical data to extract information of many types.

Chemometrics was a discipline that was really just coming into being when I finished my degree in 1984. In fact, when I started my thesis, nobody at the University of Santiago de Compostela was working in the field of chemometrics: I was, so to speak, one of the first people to start working with these tools at USC.

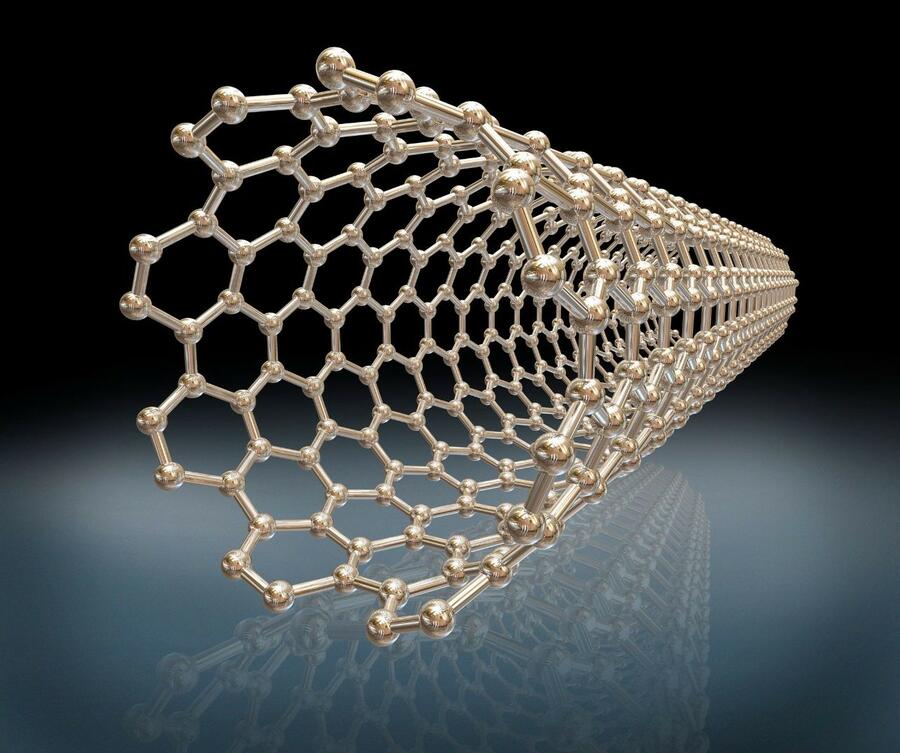

Finally, I wanted to focus on what I consider to be our third most important contribution: the use of nanotechnology. Following a talk given by Miguel Valcárcel, professor of analytical chemistry at the University of Córdoba, we made a timid foray into the world of nanotechnology. Years later, we were working extensively with carbon nanotubes, which we used as pre-concentration and metal separation systems. So far, our most cited articles are precisely related to this field.

-As you mentioned earlier, your work addressed food analysis, the classification of honey and wines, and residue detection. How and to what extent did analytical chemistry contribute to guaranteeing the quality and authenticity of food?

-We specifically developed methodologies to identify the origin of a particular product and verify its compliance with the criteria of a quality seal, which was also accompanied by work with the companies and producers themselves.

I always like to give an example of what I believe was the first of the sectors that truly committed to quality, which is Galician wine. Now, they produce high-quality, high-priced wines with high added value, which, in the end, is what it's all about.

The wine sector dared to take certain measures and carry out certain actions of great importance. Firstly, they believed in betting on quality and not quantity, on added value and not on other factors that contributed nothing to the product itself.

They also opted for the incorporation of science and technology in production and manufacturing processes. Today, the number of highly trained people who are part of the Galician wine sector is very significant: there is a high level of training from a viticultural, oenological and commercial point of view.

In the same way, honey has followed a similar path. Cheese is also undergoing the same process, with a multitude of designations of origin producing quality cheese. In short, there is a commitment to added value, to technology, to knowledge in the production process... Meat, on the other hand, such as Galician beef, is already a well-known brand. You go into a supermarket anywhere in the peninsula, and you find it with magnificent traceability as well.

In the Galician primary sector, there is no other way; it is the way we can compete with our products. They are not only good and of high quality, but they are also very typical; they are different. This typicality, together with the quality, is what will allow the primary sector to continue functioning in the way it does today. When things are well done and the product is well made, the product is successful and sells.

However, there is a problem, which is obviously the aging of the rural population. We have to start designing systems that favour the return of these young people who are so well-prepared to lead this type of company. These are companies that are very successful today, but they need a significant turnover.

-Earlier, you talked about the application of carbon nanotubes in solid-phase extraction. What advantages do these materials offer, and what practical applications do they have in chemical analysis?

-Carbon nanotubes are nothing more than cylindrical carbon tubes, made exclusively of carbon, which are nanometric in size. Although they may seem simple, they have extraordinarily attractive properties.

They are very hard and very resistant to oxidation and temperature. In other words, they are a very difficult matrix to attack from a chemical point of view and difficult to degrade. However, it is possible to modify the nanotube wall to give it certain properties.

Nanotubes also have many applications, even in industries outside of chemistry. They have applications as interesting as reinforcing the resistance of materials, as can be seen, for example, in high-level tennis rackets or surfboards.

On the other hand, focusing exclusively on my field, analytical chemistry, we can highlight various uses. In electrochemistry, which works with selective electrodes (those that are immersed in a certain type of sample and allow the concentration of a certain analyte to be determined), carbon nanotubes are very useful since they can be functionalized to work with a certain type of analyte and not with others.

We have used these nanotubes as concentration systems. By adding the nanotube to a given sample, the analyte is drawn into the nanotube itself. Then, it is sequestered, as it is very easy to separate it from the rest of the sample (especially if we give it magnetic properties), and the analyte in question goes with it. Therefore, we introduce a system into a complex sample that will react and extract the analyte of interest.

We use this technology a lot to determine the presence of metals in samples such as wastewater or water from certain types of industries, such as retail.

-In other words, this technology has great potential for determining toxicity levels, doesn't it?

-Exactly. It is also used to extract pollutants from the environment, as carbon nanotubes can sequester them. It should also be noted that, for the time being, this is an expensive technology and one whose environmental role in terms of persistence is not yet well understood. These materials are difficult to biodegrade, so it is necessary to start considering the use of this type of substance on a massive scale.

Without a doubt, this is a very interesting field of work in which there is still much to be done.

-Changing the subject a little, you were the founder of AMSLab, an applied mass spectrometry company. How did this initiative come about, and what role does technology transfer play in scientific research?

-The idea of setting up this project came about back in 2008 in collaboration with two other professors from the University of Santiago de Compostela and with the person who later became the manager of AMSLab, Manuel Lolo, who was a student of mine in analytical chemistry.

We started, then, three partners from the University plus two other partners from another company, the manager and his wife, and there was also participation from a Galician venture capital company, UNIRISCO. Between us, we provided the capital needed to get the project off the ground, and we started with 3 employees on the payroll. When I left the company in 2014, we already had 60 employees. It was what is known as a gazelle company, one that grows very quickly.

And it really was an adventure in which we learned a lot. First, because the university professors who participated knew about chemistry but not about business. The day-to-day management of a company was not part of our training, and it was something that we gradually internalized from the beginning at the Center for Business and Innovation (CEI-Nodus) of the Lugo City Council.

When the company began to take off, we started to provide specialized analysis services, especially to the pharmaceutical industry. In any case, we had to look for other alternatives, and we focused on the food and environmental fields, on the one hand, and textiles, on the other. This diversification also resulted in the diversification of the staff hired: departments began to be created, and we needed, logically, people who knew about personnel management, economics, etc.

In fact, having so many employees in so many different sectors within the company itself was a clear sign of the importance of knowledge and technology transfer. AMSLab was successful precisely because it handled a range of technologies that other analysis companies did not use. Our company could respond to challenges that other competitors could not.

In short, it was an adventure, as I said before, in which I learned a lot on a personal level, and which turned out to be very satisfying. To be able to conclude that 60 families work and develop thanks to an initiative like this, and who are satisfied with their work thanks to the good atmosphere generated, is very satisfying, isn't it?

I think it's interesting that, on many occasions, we don't dare to take the plunge. The fear of failure in our society is very pronounced, while in other places, they don't mind failing and getting back up again. And it turns out that it's the third or fourth time that they come up with the magic idea. I think you have to take risks, even if sometimes they can go wrong.

What's more, nowadays, there are many tools that weren't available before, such as systems for financing innovation. We definitely have to take advantage of them.

-Following on from this question, we wanted to ask you about the highly relevant academic and management positions at USC that stand out in your professional career. What challenges does the university face in this era from your point of view?

-I think there are several issues that we can discuss, some about the University in general, others related to the University of Santiago de Compostela specifically and others about the campus itself.

With respect to universities in general, I think we need to start thinking about how we are going to teach with the explosion of artificial intelligence. AI is going to enter the classroom, and it is going to change the way we teach in some way. It is clearly not going to replace teachers, but it is going to change the current paradigm.

With regard to teaching strategy, we also need to reflect on what the range of degrees offered by universities is going to be in such a changing, technological society. In short, a society with new ideas from the point of view of the management of this socioeconomic whole.

Therefore, some degrees will disappear, and new ones will appear, probably many of them related to this digital world of computer science and artificial intelligence.

On the other hand, focusing on our University, USC also faces another series of challenges, such as the consolidation of its position within the Spanish university system and the Galician university system. USC has been the leading University within the Galician university system, but at the moment, we have a staff that we could define as “aged.” It is essential to rejuvenate the institution with new blood and new ideas, attracting new talent.

The University has to continue in this line of quality research, good teaching and accreditation of degrees, also in sectors such as primary education. It is necessary to offer a quality and attractive product for the students, another of the greatest challenges facing USC. For geographical and demographic reasons, our University has a harder time attracting students.

That's why, thanks to the quality of our degrees, some of which are flagship courses even at the European level, such as veterinary medicine, we attract students from all corners of the world. That, in my opinion, is the right way to work.

And finally, with regard to our campus, I think the Campus Terra proposal is a smart move. Since its inception, it has always specialized in all those studies related to the primary sector: Veterinary Medicine, Forestry and Natural Environment Engineering, Agricultural and Agri-Food Engineering, etc.

Therefore, the profile of this campus is the most appropriate one. For example, in terms of its size, it is one of the campuses in Galicia with the greatest transfer, thanks to a very fluid relationship with local companies.

It is very much worth developing, investing in and having the backing of USC itself in this objective because the Lugo campus is one of the campuses that can produce the greatest number of professionals for the socioeconomic development of Galicia. All the training is important, of course, but Galicia cannot be understood without the primary sector.

So, being able to promote the local economy and commit to sustainable economic development through research and work is very rewarding. At the end of the day, what Campus Terra is also trying to do is improve the quality of life of the Galician population, especially in rural areas.